Investment in infrastructure and training is key to tapping India's sports potential

Posted by Admin on December 12, 2017

Mr. Harendra Singh and Dr. J. N. Misra

A nation of 1.2 billion with 41% ofthe population under the age of 20, India astonishes with its consistently poor performance in sports. In the Rio Olympics, India ranked 67th among 87 competing teams. When ranked according to Olympic medals per million, India was at the bottom of the list. In a fireside chat during the 2017 One Globe Forum, the topic of which was ‘Sports in India: Untapped Potential’, Dr. Jitendra Nath Misra, former Ambassador of India to Portugal and Laos, said, “Indians don’t do sports. That’s the unfortunate reality. Is it cultural? We don’t like to do physical work. Is it gender? Is it economics? What is it?”

A nation of 1.2 billion with 41% ofthe population under the age of 20, India astonishes with its consistently poor performance in sports. In the Rio Olympics, India ranked 67th among 87 competing teams. When ranked according to Olympic medals per million, India was at the bottom of the list. In a fireside chat during the 2017 One Globe Forum, the topic of which was ‘Sports in India: Untapped Potential’, Dr. Jitendra Nath Misra, former Ambassador of India to Portugal and Laos, said, “Indians don’t do sports. That’s the unfortunate reality. Is it cultural? We don’t like to do physical work. Is it gender? Is it economics? What is it?”

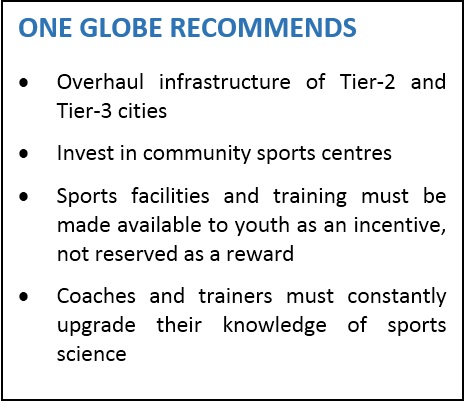

To understand why India performs so dismally at sports, Dr. Misra suggested we look at the situation under three broad heads:

His fellow panelist, Chief Coach of the Indian Junior Men’s Hockey Team and Dronacharya Award Winner, Mr. Harendra Singh, agreed that there was a serious lack of infrastructure, a problem further exacerbated by the government’s conventional approach. As an example he cited the consistent choice of metropolitan cities as venues for hosting international sporting events such as the Commonwealth or Asian games. Tier-1 cities generally do not lack infrastructure. However, their use is severely restricted. For example, Delhi’s world-class stadiums, which are highly reserved. Instead, Mr. Singh argued that if the government chose to shift focus to Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities, it would serve multiple purposes. One, it would ramp up infrastructure development, and two, it would create greater sports awareness. This is important because most Indian sportsmen come from underprivileged and rural backgrounds. If the youth in rural and semi-urban areas are exposed to sports and given access to high-class facilities from an early age, India can start to galvanise its latent talent. The investment must therefore be focused on the grassroots. More community sports centres in cities, townships and schools will be a step forward in the right direction.

Along with infrastructure, which is a mandatory requirement for a country that wants to produce top-ranked athletes, education is critical for world-class coaches. “[Sports and Science] have to come together. With the help of science, you can achieve the medal.” Mr. Singh said that Indian coaches often fail to keep up with the latest studies in sports physiology, psychology, nutrition and other key aspects of performance. For this, the government must make investment in sports training and infrastructure a priority.

This is sadly lacking. The UK, which won 67 medals in Rio, invests approximately $1.5 billion on sports infrastructure and training every year. India, on the other hand, spends $500 million on youth affairs and sports. The paucity of investment is highlighted when we compare the youth population in both countries (18-35) – 18 million (UK) versus 400 million (India).

The panelists agreed that a culture which encouraged sports rather than viewing it as a mere distraction was also key to succeeding in international sports. Mr. Singh suggested that if children could not only participate but also compete in sports from a young age, it would change the deep-seated bias that sports can never be a rewarding occupation.

It is, therefore, possible to catapult India to a leading position in the world of sports. But without dedicated government investment in infrastructure and training, even with its rich human resources India will continue to finish last.